In Stone and Story

Early Christianity in the Roman World

by Bruce W. Longenecker

Overview

Welcome!

Student eSources for each chapter of In Stone and Story include images with descriptions. Professors can access additional materials on the downloads page.

Photos on the eSources pages for In Stone and Story can be used for classroom purposes only. The copyright for these supplemental photos is held by Bruce W. Longenecker.

If you have questions about how to use these resources, please check out our Frequently Asked Questions.

Chapter 1: Human Meaning in Stone and Story

Photos

Photos 1.1 through 1.3

These photos capture three similar views of one of the most attractive entrances into Pompeii — through the Nucerian Gate. This gate is one of the gates on the town’s southern side. Other photos of the same gate are shown in figure 1.1 of In Stone and Story.

Photos 1.4 through 1.5

These are just two of the views of Mount Vesuvius as seen from the streets of Pompeii.

Photo 1.6

The Villa Regina is just over a mile to the north of Pompeii. On its grounds is a tree (shown in this photo) whose tree trunk was bent by the force of the pyroclastic flows that flowed down from Mount Vesuvius.

Photos 1.7 through 1.11

These photos show just a few of the victims of the eruption. See especially the family group in photo 1.10. In photo 1.11, the skeletons in one of the bays along Herculaneum’s waterfront compares with the skeletons in another of the bays, as shown in figure 1.3 of In Stone and Story.

Chapter 2: Fire in the Bones

Photos

Photo 2.1

The pub in which Zmyrina and Asellina worked (mentioned in chapter 2 of In Stone and Story) appears in this photo.

Photo 2.2

This photo displays the shrine that adorned the house in which Ennychus, Venidia, and Livia Acte lived. Virtually every residence had at least one devotional shrine within it (as discussed at various points in In Stone and Story).

Chapter 3: Accessing the First-Century World

Photos

Photos 3.1 through 3.5

These photos depict a few things of interest pertaining to the Vesuvian towns. Photos 3.1 and 3.2 show how Herculaneum has been released from its volcanic encasement through modern excavations. Photo 3.3 shows how archaeologists have removed some of the artwork from the walls of Vesuvian residences and places of business (in this case, the House of Lucretius in Pompeii), in order to be housed elsewhere (and often displayed in the National Archaeological Museum of Naples). A first-century dining room is shown in photo 3.4, with a triclinium (a “three-bed” arrangement) around the central area in which food would have been brought to the people dining by slaves, and with a cascading water feature flowing down the back wall. Water was transported to many residences of the town’s wealthier residents by water pipes, as in photo 3.5.

Chapter 4: Deities and Temples

Photos

Photo 4.1

Figure 4.1 in In Stone and Story needed to be printed rather small on the page. This jpg allows the same figure to be used beyond those constraints.Photos

4.2 through 4.7

Three of Pompeii’s main temples are highlighted in these photos. Photo 4.2 depicts the temple of Jupiter (in the center of the photo, and at the head of the civic forum), with Mount Vesuvius looming in the background late in the afternoon. The next four photos showcase the temple of Apollo (also situated on the civic forum) — the statue of Apollo (photo 4.3 and photo 4.4), the temple’s sacrificial altar (photo 4.5) and the steps leading up to the main temple precinct (photo 4.6). The foundations of the temple of Venus are shown in photo 4.7, which demonstrates somewhat how that temple overlooked the sea (as mentioned on page 40 of In Stone and Story).

Photos 4.8 through 4.12

The “Sacred Area” on the shore of Herculaneum housed several temples, including a temple to “the Four Deities.” Reliefs hung from the podium of this temple, depicting the four deities (as shown in photo 4.8) — Vulcan (photo 4.9), Neptune (photo 4.10), Mercury (photo 4.11), and Minerva (photo 4.12). These were deities that were thought to enhance business and trade (among other things).

Photo 4.13 and 4.14

Figure 4.9 in In Stone and Story depicts a craftworker’s shop. These two photos give more context to that figure, showing more of the ground floor area (photo 4.13) and the stairs leading up to a small bedroom area (photo 4.14).

Chapter 5: Sacrifice and Sin

Photos

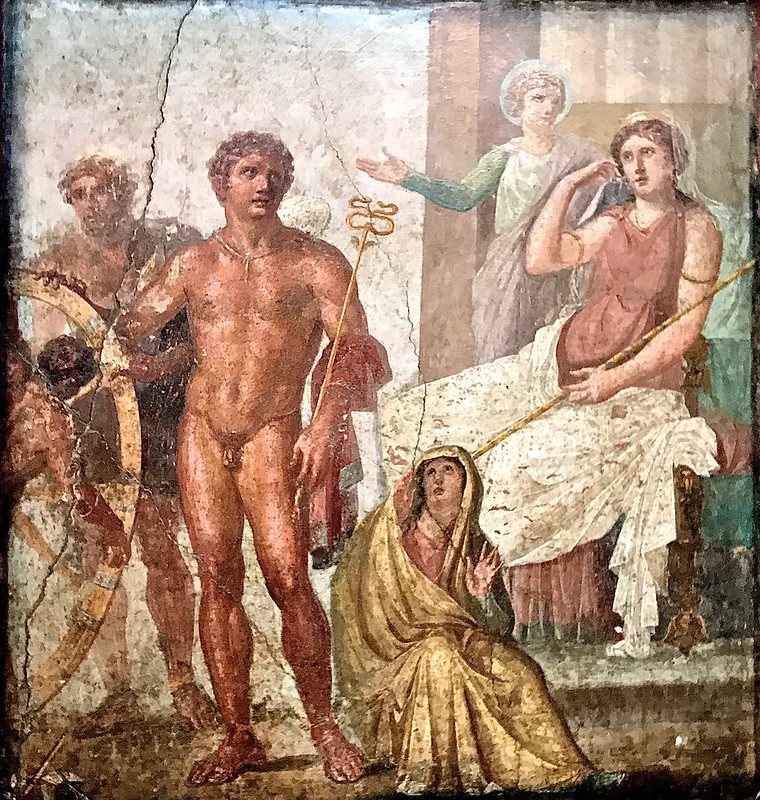

Photo 5.1

This fresco (from the House of the Vettii) portrays a famous scene in Greek mythology – the punishment of Ixion. In the story, Ixion both murders his father-in-law and attempts to seduce Juno (or Hera in Greek nomenclature), the wife of Jupiter (or Zeus) — two heinous relational sins. For these offenses, Jupiter orders Mercury (or Hermes) to bind Ixion to a spinning wheel forever. In this fresco, the far left shows Ixion bound to the wheel; Mercury is toward the middle and Juno is seated on her throne to the right. Other lesser characters in the story are also depicted.

Photo 5.2

Figure 5.9 of In Stone and Story offered a view from the front of the macellum of Pompeii. This photo offers another view of the macellum, this time from behind the stalls where meat was sold after having been offered to a deity in a nearby temple. This section of the macellum appears in the top left corner of figure 5.9 of In Stone and Story.

Chapter 6: Peace and Security

Photos

Photos 6.1 through 6.5

Chapter six of In Stone and Story highlights the importance of Eumachia for the town of Pompeii. Photo 6.1 shows the statue of Eumachia (see In Stone and Story figure 6.2). The full inscription over back entrance to the Eumachia building is shown in photo 6.2, advertising Augustan concord and piety (compare the massive inscription at the front of the Eumachia building, shown in In Stone and Story figure 6.3). The front of the Eumachia building had two statue bays to the left of the entryway, where statues of Aeneus and Romulus were placed, along with inscriptions in their honor (see photo 6.3). The interior of the Eumachia building is shown in photo 6.4. When Eumachia died, she was memorialized in a massive tomb (captured in photo 6.5) in a necropolis to the south of Pompeii.

Photo 6.6

The three “Capitoline deities” of Roman success are depicted in this photo, with the three deities together in a Pompeian lamp, together with the eagle emblem that represented Rome in its full glory.

Photo 6.7

This photo depicts the podium for political speeches in Herculaneum. It is possibly not wholly coincidental that the speakers’ podium is placed right next to an entryway into the College of the Augustales (a powerful group dedicated to the Roman political order, discussed especially in In Stone and Story chapters 11 and 13). This must have had the effect of ensuring that speeches delivered from this podium were in alignment with the political ideology of the day.

Chapter 7: Genius and Emperor

Photos

Photos 7.1 and 7.2

The conviction that spiritual forces are involved in any configuration of power is evidenced in the many neighborhood shrines that are found in Pompeii — where residents can enhance the spirit of the neighborhood through sacrifices. When archaeologists discovered the shrine depicted in photo 7.1, they noticed that it still had chicken bones on it — from a sacrifice that must have preceded the eruption perhaps by only a matter of hours.

Photos 7.3 and 7.4

Enhancing protection often involved depicting animals in mosaics at the entryways of houses — thereby calling upon the protective spirit of those animals. These two photos depict two non-canine mosaics of this kind — a wounded bear and a wild boar (as mentioned on page 82 of In Stone and Story; see also figure 7.4 of In Stone and Story).

Chapter 8: Mysteries and Knowledge

Photos

Photos 8.1 through 8.4

These photos show a few further depictions of Bacchus from the Vesuvian towns. Photo 8.1 is a fresco of Bacchus as a youth; photo 8.2 is a bas relief of Bacchus with his panther, holding a cornucopia of plenty; and photo 8.3 is a fresco of Bacchus seeing Ariadne (in deep sleep) for the first time. The garden in the house of Marcus Lucretius (at 9.3.5) was adorned with statues of Bacchus in various depictions, as illustrated in photo 8.4.

Photo 8.5

A vase depicts a scene of Bacchic celebration, with the mythic Silenus joining two women sharing wine.

Photo 8.6

A young woman being prepared for marriage is an important component of the fresco in the Bacchic room in the Villa of the Mysteries.

Photo 8.7

This photo shows a collection of amphorae for the storage of wine, from a wine shop in Herculaneum (from 5.6).

Chapter 9: Death and Life

Photos

Photo 9.1

This Pompeian figurine depicts Isis enthroned, holding a cornucopia of plenty.

Photos 9.2 through 9.9

Each of these photos of Pompeian artifacts (except photo 9.2, which is a modern model) illustrates an aspect of Isis-devotion.

- Photo 9.2 models the temple of Isis as it would have looked prior to the eruption (and notice the large banquet room on the premises of the temple, to the right of the photo).

- A ceremony of Isis-worship is depicted in the fresco of photo 9.3.

- Photos 9.4 through to 9.6 all depict frescos from the temple of Isis that depict priests of Isis.

- Another fresco of a priest of Isis is shown in photo 9.7 (from the House of Octavius Quartio).

- Each priest depicted in photos 9.6 and 9.7 is holding a sistrum — a kind of rattle that was used in the worship of Isis.

- Pompeian décor often featured a sistrum, as in photo 9.8 (décor from the wall of the temple of Isis in Pompeii) and photo 9.9 (décor from the wall of the House of the Golden Cupid).

Chapter 10: Prominence and Character

Photos

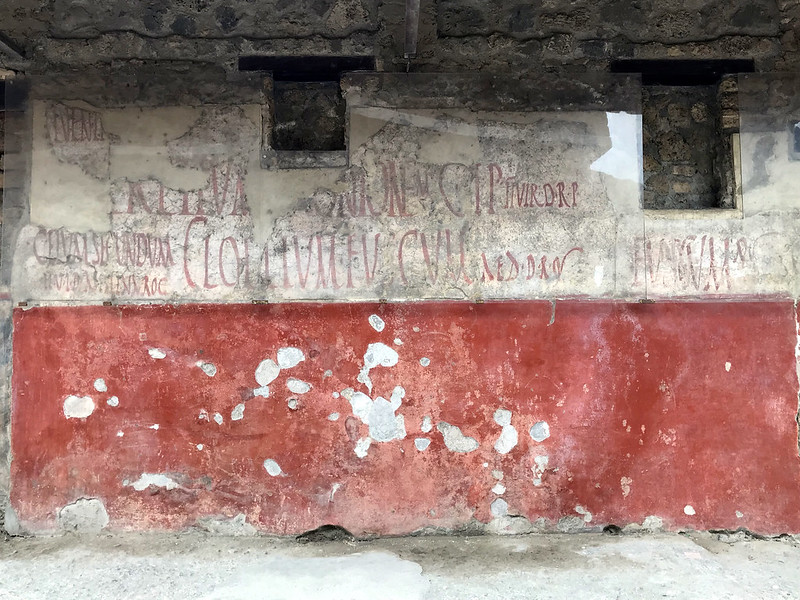

Photos 10.1 and 10.2

These are two examples of election endorsements (called dipinti) found on the external walls of buildings in Pompeii (see also figures 10.4 and 10.5 in In Stone and Story). The second of these photos shows an endorsement calling on people to vote for Gnaeus Helvius Sabinus. There were over 100 election endorsements for Sabinus, none of which had been painted over by later notices. This suggests that Sabinus had campaigned in the spring of 79, having taken office in July of that year (on the likely assumption that he won the vote). Unfortunately, his time in office was cut short by the eruption of Vesuvius in the fall of that same year.

Photos 10.3 and 10.4

Two statues stood on either side of the entrance of the corridor allowing the civic elite to enter the amphitheater. The statues were of “Gaius Cuspius Pansa, son of Gaius, father” (C[aius] Cuspius C[aius] f[ilius] Pansa pater) and his son “Gaius Cuspius Pansa, son of Gaius.” These photos show the inscriptions at the base of the statue bays, with the names prominently displayed below the statues and with their positions of honor listed as well. After the earthquake that shook Pompeii in 62, funding for the restoration of the amphitheater was substantially provided by these two men.

Photo 10.5

From this photo (of inscription CIL 10.854), we can see that a man named Titus Atullius Celer donated money to sponsor the rebuilding of the amphitheater after the earthquake of 62. In particular, he donated a section of the seating in the amphitheater. The beginning of the full inscription reads as follows:

T = Titus

Atullius = the family name, Atullius

C F = son of Gaius/Caius (F = filius, or “son”)

Celer = his public name

++ V = duovir (magistrate)

Photo 10.6

Statue bases can be found in several locations in Pompeii’s forum. On them stood statues of prominent civic leaders who were publicly memorialized by the town council for their benefaction to the people.

Photo 10.7

In “the gem cutter shop” of Herculaneum was found this herm (that is, a sculpture of a person’s head and perhaps upper body). It depicts a male who was most likely the householder. Setting up this herm in a central place within the shop was a gesture to his prominence within the household (and perhaps beyond).

Chapter 11: Money and Influence

Photos

Photo 11.1

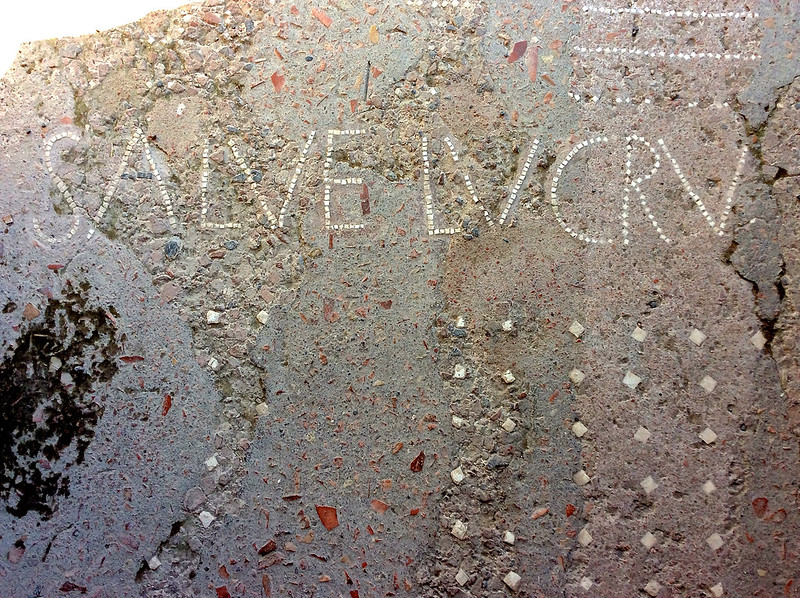

People who entered the House of Siricus in Pompeii (7.1.47) were greeted with a slogan embedded in a mosaic — salve lucrum, or “hail profit” (CIL 10.874).

Photo 11.2

Chapter 11 of In Stone and Story makes mention of Quinctius Valgus and Marcus Porcius — Pompeii’s earliest mayors, or duoviri. One inscription dedicated to them is shown in figure 11.2 of that chapter. This photo shows the other Pompeian inscription dedicated to them — this one hanging in the corridor of the “theater section,” honoring them for their benefaction to the people.

Photo 11.3

When Pompeii’s macellum (or “market”) was restored after the eruption of 62, these two statues were placed front and center in the restored complex. There is some debate as to who the male and female figures are, but the best guess is that they are the husband and wife who sponsored the restoration of the macellum.

Photo 11.4

A tomb honoring Gaius Munatius Faustus (who is discussed together with his important wife Naevoleia in chapter 19 of In Stone and Story) displays a boat at sea, probably illustrating how Faustus had made his money in the shipping industry.

Photo 11.5

The significant thing to notice in this photo is the extent to which steps adjacent to the entryway of Julia Felix’s country club (which takes up the whole block of insula 2.4) extend relatively far out into the street. Town officials generally wanted to ensure that traffic would move effectively through the town. The fact that these steps would have interrupted the smooth flow of traffic along one of the town’s most important streets suggests that the household must have had significant influence with the town officials.

Photos 11.6 through 11.9

Chapter 11 of In Stone and Story highlights the significance of the Augustales. These photos depict a few more of the archaeological evidence of the Augustales in the Vesuvian towns.

- Part of the interior of the so-called College of the Augustales in Herculaneum is shown in photo 11.6, and an inscription in the interior remembers a dinner in honor of the emperor, paid for by two brothers (photo 11.7).

- The tomb of Gaius Calventius Quietus remembers him to have been an Augustalis, and displays this graphically through the use of a wreath (photo 11.8); another wreath was displayed on the other side of the tomb as well. (Note that someone with the same name stood for civic election during the Neronian period, probably the son of the man memorialized here. It is possible, then, that the father had been a slave who earned his freedom and became a prominent Augustalis, and that his freeborn son was then free to enter political office — something that the father could not have done if he had been a slave at any point in his life.)

- In photo 11.9, a house is shown to display a wreath above its entryway, probably signaling that an Augustalis lived there and wanted everyone to know this prominent aspect of his status.

Photo 11.10

Boats were a significant part of the economy of the Vesuvian seaside towns. One boat was recovered from the bay of Herculaneum, as depicted in this photo. The boat was more than thirty feet long and had six oars, three on each side. Probably the boat needed four people to navigate it: one person at the rudder, and three people at each pair of oars.

Photos 11.11 and 11.12

In Herculaneum, the so-called House of the Stag overlooked the sea, having a prominent place on the ancient shoreline. The first of these photos shows something of what that might have been like, although the view now looks out onto the high wall of volcanic debris that entombed the town during the eruption (photo 11.11). Photo 11.12 is the reverse view, showing the position of the house over the town’s shores.

Chapter 12: Literacies and Status

Photos

Photo 12.1

The charred remains of a wax table are shown here — the usual medium for writing down everyday information. A stylus, also shown here, would be used to inscribe the information into the wax. When the information was no longer needed, the stylus could be used to rub out the information and restore the wax to a “clean slate” condition.

Photos 12.2 through 12.4

These photos capture the graffiti inscribed into walls by the ordinary people of Pompeii.

- Photo 12.2 shows graffiti from the interior walls of Pompeii’s main brothel (notice “Victor”).

- The graffiti in photo 12.3 are from the passageway to the theater complex in Pompeii, and include the word vale (hello).

- Math calculations from the same passageway are shown in photo 12.4.

Photos 12.5 through 12.7

Also inscribed on walls are these three incisions depicting gladiators (discussed especially in chapter 13 of In Stone and Story). Notably, the names of these gladiators appear above their image: Albanus (photo 12.5), Severus (photo 12.6), and Aracintus (photo 12.7).

Chapter 13: Combat and Courts

Photos

Photo 13.1

This is a fresco of the divine Victory crowning a warrior who has succeeded in defeating his competitors (from Pompeii’s macellum).

Photo 13.2

This dagger and sheath was discovered in Herculaneum — just one of many similar artifacts discovered in the Vesuvian towns.

Photos 13.3 and 13.4

Pompeii’s walls testify to its own history of combat. These northern defensive walls show the marks of ballistic projectiles catapulted against them by Roman forces in the Social War of 91–89 BCE, as in photo 13.3. One of Pompeii’s twelve defensive towers is shown in photo 13.4.

Photos 13.5 and 13.6

Chapter 13 of In Stone and Story takes time to discuss social combat in the courts. The courts of Pompeii were held in the basilica. These two photos give further indication of the powerful austerity of the court context, with massive columns (holding up a roof structure) accentuating the gravitas of the Roman legal system.

Chapter 14: Business and Success

Photos

Photos 14.1 and 14.2

Figure 14.8 of In Stone and Story depicts a frescoed shrine overlooking the countertop of a fast-food and wine bar. Photo 14.1 shows more of the context in which that frescoed shrine is found, including the countertop of the bar and the “dolia” in which the bar’s items for sale were kept. The photo also shows back rooms where customers could eat in slightly more formal settings. Photo 14.2 illustrates another strategy for protecting a business — not putting deity on display within the business premises (as in photo 14.1) but locating the deity above the entryway of the business. The shrine for a deity is clearly located directly above the bar’s countertop.

Photos 14.3 through 14.6

Photo 14.3 shows three frescos painted onto the wall of a small bar (at 6.10.19). There are no deities or spiritual beings or mythic scenes in these frescos. The scenes depict moments in ordinary life. In the scene on the far left, gamblers throw dice (photo 14.4). In the middle scene, a slave serves a customer (photo 14.5). The scene on the far right is hard to decipher now (photo 14.6), but early records of it clearly indicate that it depicted people sitting together (with one drinking a cup of wine to his mouth), with various foods hanging from a wall near them.

Photo 14.7

A bar near the Herculaneum Gate into and out of Pompeii (at 6.1.2) has a small seating section that extends into the pedestrian pavement, allowing more customers to frequent the bar at any time — a fairly unique and somewhat surprising architectural feature.

Photo 14.8

This wine shop in Herculaneum is typical of small Vesuvian workshops and business premises. The shop itself is open to the street at ground level; the amphorae containing the wine was held in the wooden racks at the back of the shop; a ladder leads up to a higher floor, which probably served as a small bedroom for the workers and their family members.

Photos 14.9 and 14.10

To ensure that grain was bought and sold fairly, a measuring station was placed in the forum of Pompeii (photo 14.9), allowing for a degree of exactitude when measuring out quantities of produce. (Compare the saying of Matt 7:2 — “with the measure you use, it will be measured to you.”) When business was conducted through contracts, parties in the business agreement often used stamp rings (photo 14.10) to validate the contract, pressing their identification stamps into wax tablets to signal their approval of the contract.

Chapter 15: Household and Slaves

Photos

Photo 15.1

The kitchen in Pompeii’s Villa of the Mysteries reveals something quite common in Vesuvian residences — that is, a shrine is often placed prominently within kitchens or other rooms usually heavily populated by slaves. As a consequence, the deities of the household overlook the slaves in their work, as if to ensure that the householder will get the most out of the household’s human workforce.

Photos 15.2 through 15.4

Oddly (at least to our modern mind), kitchens and household toilets were often placed side-by-side in Vesuvian residences. In photo 15.2, the toilet is to the left and the cooking platforms are to the right (in Herculaneum’s House of the Double Atrium). Photos 15.3 and 15.4 show the kitchen/toilet combination in Pompeii’s House of the Tragic Poet. The view into the kitchen is shown in photo 15.3, revealing where the food was cooked; photo 15.4 reverses the view out of the room, revealing the toilet area to the left, adjacent to the doorway.

Photos 15.5 and 15.6

The House of the Bicentenary in Pompeii was a fairly well-off residence. These photos show a two-seater toilet (photo 15.5), which was used by household slaves (and perhaps others). One of the household’s slaves was a woman named Martha — a Judean (since the name was almost exclusively given to Judean women). We know her name from a graffito etched into the plaster across from the two-seater toilet (as shown in photo 15.6). It read: “This is Martha’s triclinium. She defecates in her triclinium” (CIL 4.5244 — a graffito discussed briefly in chapter 12 of In Stone and Story). Since a triclinium was a dining room for the householder and his/her guests, placing the notions of a triclinium and a toilet together was a way that someone in the household poked fun at Martha. Was she able to read the insult?

Chapter 16: Family and Solidarity

Photos

Photo 16.1

It is not uncommon to find a herm of householders within Vesuvian residences (as in photo 10.7). This herm captures the likeness of the householder of the residence that archaeologists now call the House of the Bronze Herm (for obvious reasons). It was a way of reinforcing the identity of the person around whom the whole of the life of the household was to orbit.

Photo 16.2

Some archaeological remains from the Vesuvian towns are poignantly illustrative of the bonds of solidarity within family units — especially when we see family members together being overcome by the eruption in death. This seems to have been the case for the group of four people shown in this photo (whose body cavities were among the first to be filled with plaster back in the nineteenth century, in a location now called “Skeleton’s Alley”; these plaster casts are currently on display in the House of Publius Vedius Siricus). The person on the right is the only male in the group, and his posture suggests to archaeologists that he was leading the way. At the back of the group was a female, seemingly the eldest of the three females who held something precious to her chest (perhaps jewelry or coins?). Between these two was a young girl (whose plaster cast was virtually destroyed in the Allied bombing of Pompeii in 1943) and a young adult woman (shown on the left of this photo). (Another family caught in the disaster is shown in photo 1.10.)

Photos 16.3 and 16.4

If families died together in the disaster, they were often buried together prior to the disaster. Photo 16.3 shows statues from a tomb in the necropolis at Pompeii’s Herculaneum Gate — the tomb of the Ceii household (HGE39 and HGE39A). We cannot be certain that these all derive from the same tomb, since we do not have accurate record of their find spots. But it has been argued that most or all of these statues originally belonged together in the family tomb, representing different members of the reputable family, both male and female, with men in Roman togas and women in fine garments. Less wealthy families often found less expensive ways of being buried together, as illustrated by photo 16.4. Here headstones (or columellae) serve as memorials of the dead for members of a household, who were buried near to each other as death took them successively over the years.

Chapter 17: Piety and Pragmatism

Photos

Photos 17.1 through 17.3

In the Roman world, meals were often social events that enhanced both people’s sense of belonging and their sense of status. Photo 17.1 is a fresco showing women preparing themselves for an event of some kind, perhaps a gathering for a meal in a nearby household. A woman’s necklace (no doubt worn at social events such as meals) is displayed in photo 17.2. Although it consists of beautiful beads, notice also that it has two phallic pieces as well. These were not erotic images, of course; they helped offer the woman protection (as discussed especially in chapter 18 of In Stone and Story). A stylized depiction of a male and female enjoying a banquet is found in photo 17.3 (MANN 9554).

Photos 17.4 through 17.6

Social dining took place in a variety of situations — sometimes in fairly large dining rooms (such as the one in the House of the Cryptoporticus, shown in photo 17.4), or outdoor triclinia (as in photo 17.5), or in temple dining halls (such as the one attached to Pompeii’s Temple of Isis, shown in photo 17.6; see also photo 9.2; compare Paul’s discussion in 1 Corinthians 8:10 of “eating in the temple of an idol”).

Photo 17.7

Photo 17.7 of a snake fresco (the protective spirit of the location, at 1.11.11) amplifies what is displayed in figure 17.6 of In Stone and Story.

Chapter 18: Powers and Protection

Photos

Photo 18.1 and 18.2

Since water was a precious commodity, Pompeians wanted to protect it, including protection from malevolent spiritual forces. To do this, they painted spiritual beings above the water intake channel as it flowed into the town from the springs of Serino (in the Avellino province of Italy). The spiritual beings are probably a river deity and three nymphs, shown close-up in photo 18.1 and in context in photo 18.2.

Photos 18.3 and 18.4

Since spiritual forces could be involved in any aspect of life, counter measures were needed, as evidenced in architectural features throughout the Vesuvian towns. Photo 18.3 shows an outdoor dining area that benefitted from spiritual protection, with shrines for deities standing above the triclinium where diners would be eating. A face made out of terra cotta was positioned in the external wall of a residence (6.1.4; see photo 14.5). Because of its resemblance to a similar artifact found over the entrance of the House of the Double Atrium in Herculaneum, this is probably a Gorgon face that was used to ward off evil and preserve the residence from malevolent spiritual attacks.

Photos 18.5 through 18.8

Hundreds of Vesuvian artifacts feature the phallic symbol — a symbol used throughout the Vesuvian towns because it was thought to be a potent source of protection against spiritual onslaught (as discussed especially in chapter 18 of In Stone and Story). These photos offer some indication of the ubiquity of this symbol.

- Photo 18.5 shows how the symbol was incorporated into the frescoed décor of a bedroom in Villa A at Oplontis.

- Someone thought it would be beneficial to construct a belt with the phallic symbol strung around the whole of his body (as in photo 18.6).

- Photo 18.7 shows one of the many phallic symbols placed for protection on the exterior of residences (see also figure 18.4 of *In Stone and Story*).

- Someone chiseled a phallic symbol into a paving stone on the street in front of his residence (photo 18.8) — a gesture that may have also pointed the way to a local brothel while also adding protection to the locale.

Chapter 19: Banqueting and the Dead

Photos

Photos 19.1 through 19.2

These photos feature particular columellae (see also photo 16.4). A columella in the center of photo 19.1 clearly shows the name of the person it memorializes — a woman (now unknown) named Claudia Aucta. Photo 19.2 shows the columellae of two men and one woman. We know this because columellae commemorating women always are marked out by a hair bun at the back of the head, something that columella commemorating men never had.

Photos 19.3 through 19.4

Figure 19.7 of In Stone and Story shows a drawing of a triclinium in a tomb — a drawing that dated close to the time that the tomb was excavated. Since then the tomb (like most of the excavated parts of the Vesuvian towns) has been ravished by the forces of nature, causing the site to look much different today. Photo 19.3 shows what the triclinium looked like in 2015. The façade of the tomb is shown in photo 19.4. The tomb is that of Gnaeus Vibrius Saturninus (HGW23).

Photos 19.5 through 19.9

The tomb at HGW17 has a marble inscription in honor of Aulus Umbricius Scaurus, a notable civic official of Pompeii (mentioned in chapter 10 and 13 of In Stone and Story). As noted in the descriptor for figure 10.3 of In Stone and Story, archaeologists may have placed the inscription on the wrong tomb, since it had fallen off its moorings in the eruption and was found between HGW16 and HGW17. But despite the issue of who this tomb commemorated, it is a good indication of the architecture of a memorial tomb and its social configuration — including 15 niches (not all of them shown in these photos) into which cremation vessels would have been placed, and a back area for household memorial gatherings. The photos reveal:

- the façade of the tomb (photo 19.5);

- the entrance into the inner tomb, with a central space for the placement of the householder’s cremation vessel (photo 19.6);

- the left side of the inner tomb (with the photo taken from the front looking back), with four further niches for cremation vessels at the side and one more shown along the back wall (photo 19.7);

- the right side of the inner tomb (with the photo taken from the back looking toward the front), with four further niches at the side and one more shown along the front wall (photo 19.8);

- the back area of the tomb enclosure (photo 19.9), allowing just enough space for a household gathering in order to honor the deceased of the household.

Overview

Welcome!

Student eSources for Reading the New Testament as Christian Scripture include study questions, videos, and flashcards of key terms. Professors can access additional materials on the downloads page.

If you have questions about how to use these resources, please check out our Frequently Asked Questions.

Chapter 1: The New Testament as Christian Scripture

Study Questions

- How does the NT relate to the OT? How is this understanding different or similar to the way you thought about the two Testaments before reading this chapter?

- Why is it important that we call the OT and NT “Scripture”? How does this influence the way we read them?

- What is the definition of “canon”?

- Memorize Matthew 5:17.